I don't know what more you want me to say which isn't saying what I've already said countless times.

Take a regular torch. It's not the sun. But it doesn't need to be because light behaves in exactly the same fashion (with one or two exceptions which really only apply in theoretical environments).

The Inverse Square Law states that

light intensity is inversely proportional to the square of the distance to the source. Roughly translated this means that you lose the MOST of your light CLOSEST to where it originates and as the distance increases this falloff diminishes toward zero

at an ever diminishing rate without ever reaching zero.

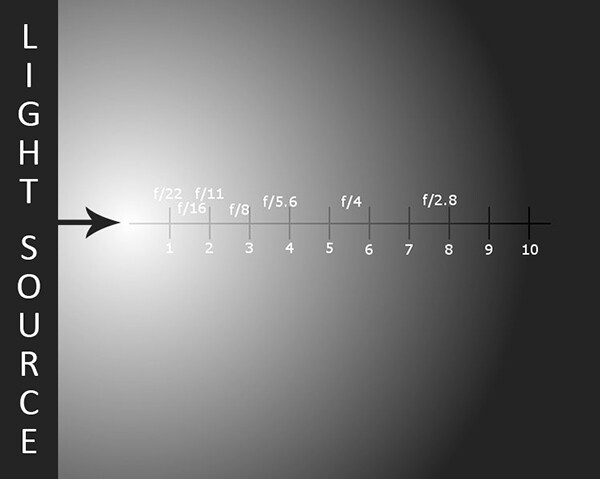

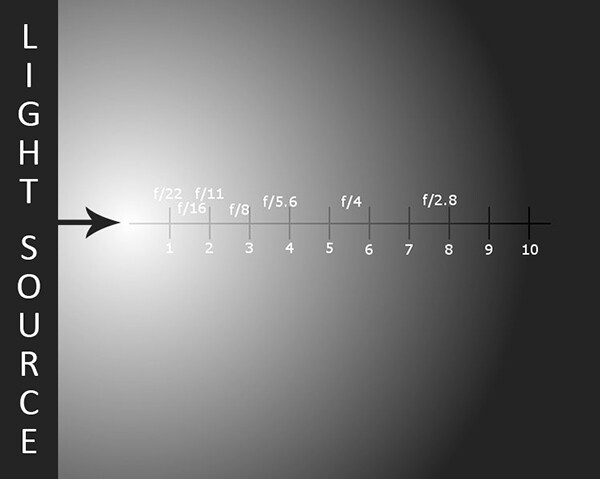

In the illustration above HALF of the total output will be lost in the first few inches. Double the distance and it is reduced to a quarter and so on etc. But the important point in relation to this discussion is what's taking place at the other end of the scale. The reason we see starlight across vast distances is because even though its intensity is ALWAYS falling - the further light travels from the source the longer it takes to do so. Plug the numbers into any calculator and you can immediately verify this.

If the Apollo photographs are genuine then the single light source illuminating the subject (the sun) is 150 million km away. At that distance most of its intensity has been diluted and the rate of falloff drops to negligible levels. Sure, it's still higher than what it would be if we were viewing the sun from the other side of the galaxy. But we aren't seeing the kind of colossal bites taken out of luminosity that we witnessed early on.

Consequently we should see

no appreciable difference in the luminosity of any part of the moon exposed to direct sunlight and not interfered with by shadow. Now, there are some complicating factors relating to a variety of issues which can result in the distant background looking slightly duller and/or desaturated (especially on the earth where this question is further complicated by our atmosphere which scatters light and can function as an enormous softbox).

But if you are looking at an Apollo photograph in which there are significant differences in luminosity that would require you to alter your camera's shutter speed and/or f/stop to correctly expose each area - and these discrepancies cannot be explained by the sun's light being obscured by some object - it has either been

tampered with in post-production or it was

photographed in a studio environment.

The reason I say the latter is because we ALREADY KNOW that light intensity can fall-off in pretty dramatic fashion - provided the source of light is CLOSE TO the subject (compare position 1 to position 4 in the illustration).

I'm clueless as to how pointing out this simple and obvious truth has morphed into wild accusations about the moon being a hologram and such. This argument is strictly confined to the validity of the Apollo photographs - although I do think it has wider implications insofar as NASA's trustworthiness is concerned.

Take a look at the original NASA stock. We see this issue cropping up time and time again (notice I DO NOT say ALL). Just as we see other problems such as harshly backlit subjects which - despite the astronauts carrying NO SECONDARY SOURCES OF ILLUMINATION - are perfectly illuminated from the front.

Bear in mind that in order to achieve the above you have to supply CLOSE TO the same amount of light in the opposite direction in order bring the subject within the tonal range of the camera. Which means you either have to set up a portable flash-unit to fill in the shadow areas - or (maybe) use a very efficient reflector (neither of which the astronauts carried). Without it the subject MUST BE reduced to a pitch-black silhouette.

There's simply no room for debate on this question. Don't believe me? Try it yourself. It isn't a difficult experiment to set up.

This is why I draw the distinction between natural light and theatrical (make-believe) light.

Now, if you don't mind I'm calling it quits on repeating the SAME THING OVER AND OVER AND OVER AGAIN. Quite frankly, I'm bored rigid with the whole issue and there's only so much stupidity I can take.

I mean, if you have any genuine interest in this question you'll spend five minutes setting up two or three simple experiments which will tell you more about photography and light than NASA seems willing to divulge. It really is THAT SIMPLE.